The History of Angkor

The wall of the city is some five miles in circumference. It has five gates, each with double portals. Two gates pierce the eastern side; the other sides have one gate only. Outside the wall stretches a great moat, across which access to the city is given by massive causeways. Flanking the causeways on each side are 54 divinities resembling warlords in stone, huge and terrifying. All five gates are similar. The parapets of the causeways are of solid stone, carved to represent nine-headed serpents. The 54 divinities grasp the serpents with their hands, seemingly to prevent their escape. Above each gate are grouped five gigantic heads of Buddha, four of them facing the four cardinal points of the compass, the fifth, brilliant with gold, holds a central position.

This is how Chou Ta-Kuan, a Chinese diplomat, described the Khmer capital of Angkor Thom during his visit in the late 13th century in his account The Customs of Cambodia. The visitor from the north was clearly impressed by the power and affluence projected by the city’s monuments, which, at the time, were the culmination of 500 years of the rise and fall of one of the greatest empires of the Middle Ages. To put the glory of Angkor in perspective: When Chou Ta-Kuan visited, the imperial city of Angkor Thom had around one million inhabitants, and the temple of Ta Prohm alone had more than 80,000 servants and staff, while in Europe, Paris had a population of just 25,000.

The history of Angkor begins some 500 years prior to Chou Ta-Kuan’s visit, at the dawn of the 9th century. In the preceding centuries, smaller empires and fiefdoms had fallen and risen in the region we now recognize as Cambodia. Most of them had fallen under the control of the court of Java in Indonesia, although some recent studies suggest that Java could in fact be Chenla, an earlier Khmer kingdom. Whatever the case, the first great Khmer king, Jayavarman II (A.D. 802–850) declared himself devaraja (divine ruler) of the kingdom of Kambujadesa; he established several capitals, including one at Phnom Kulen, northeast of Siem Reap, and later another at Hariharalaya, near Roluos.

Toward the end of the 9th century, Indravarman I (A.D. 877–889) built the first of the great Angkor temples, Preah Ko, as well as the Bakong, and began work on a huge baray (water reservoir) at Hariharalaya. His son, Yasovarman I (A.D. 889–900) expanded on his father’s achievements, finished the baray, and created yet another royal city, Yashodarapura, located around Phnom Bakheng, today’s most popular sunset spot within the Angkor Archaeological Park. Yasovarman I might also have been the Khmer king who began construction of the mountain temple of Preah Vihear. Other kings came and went, powers struggles among different royal families and with the neighboring Cham continued, and the capital briefly moved out to Koh Ker before returning to the Angkor area.

Suryavarman II, who ascended the throne in 1113, extended the Khmer Empire to its largest territory. He also built Angkor Wat, yet following his death in 1150, the empire fell apart once more. Only his cousin, Jayavarman VII, managed to reunite the kingdom under the crown in 1181, fight off the Cham, and commence the Khmer Empire’s last great renaissance. Jayavarman VII converted from Hinduism to Mahayana Buddhism, founded the last great Khmer city, Angkor Thom, and oversaw Angkor’s most prolific period of monument building. In less than 40 years, hundreds of temples—as well as libraries, dharamshalas (rest houses), and hospitals—were hastily constructed along new roads that now connected large parts of the kingdom. Many of the monuments built under Jayavarman VII are artistically inferior and stylistically impure because the speed of construction was so frenetic. It seemed like the last god-king knew that time was running out. Jayavarman VII had some of Angkor’s most enduring iconic buildings constructed, including Ta Prohm and the Bayon. In 1203, the king annexed Champa and effectively extended his empire to southern Vietnam. But with the death of Jayavarman VII in 1218, the moment had passed, and Angkor slowly went into decline.

Hinduism was briefly reintroduced by Jayavarman VIII in the late 13th century, resulting in a concerted and presumably costly act of vandalism that saw the defacing of many Buddhist monuments, including Ta Prohm and Preah Khan. Buddhism soon returned, but in a different form, Theravada Buddhism, which puts less emphasis on the divinity of the king; it has survived in Cambodia to this day. Perhaps this loss of spiritual authority affected later kings. Perhaps, as new research suggests, the Angkor Empire had overreached, ruined the environment around Siem Reap, and was ready to give way to something else.

Repeated incursions by the Siamese culminated in a seven-month siege of Angkor Thom in 1431, after which King Ponhea Yat moved the capital southwest to Phnom Penh. Other reasons for the demise of this great empire are also plausible. The Khmer Empire had been built on the back of an agrarian society, and trade was becoming more important in Southeast Asia. Angkor Thom was too isolated, too far from the coast, and too far from the Mekong River to be able to keep up with new challenges. Following the move to Phnom Penh, the temples remained active, yet were slowly taken over by the forest.

“REDISCOVERY” OF ANGKOR

Angkor is unlikely ever to have been completely abandoned, although precise information on the activities around the ruins between the 15th and 18th centuries is sketchy. Following the last onslaught by the Thais in 1431 and the gradual shift of the capital toward Phnom Penh, monks continued to live around Angkor Wat until the 16th century. The Cambodian court apparently returned to Angkor for brief periods during the 16th and 17th centuries.

CHOU TA-KUAN: ANGKOR’S CHRONICLER

Chou Ta-Kuan, a Chinese diplomat in the service of Emperor Chengzong of Yuan, grandson of Kublai Khan, traveled from Wenzhou, on the East China Sea coast, past Guangzhou and Hainan, along Vietnam’s coast, and up the Mekong River as far as Kompong Cham, from where he took a smaller vessel across Tonlé Sap Lake to arrive at the imperial city of Angkor Thom in August 1296. Chou Ta-Kuan was neither the first nor the last Chinese diplomat to visit the seat of the Angkor Empire, but he stayed for 11 months and took notes. The Customs of Cambodia, the only surviving first-person account of life in the Khmer Empire, is one of the most important sources available to scholars and laypeople to understand Angkor. Not only did the diplomat describe the city of Angkor Thom, he also shed some light on the daily lives of ordinary Cambodians. With his report, Chou Ta-Kuan gives today’s visitors an opportunity to imagine how the ruined splendor of the temples must once have been a busy metropolis and how, at its height, a million people could have lived and worked here.

Around the same time, an early report by the Portuguese writer Diego De Couto apparently referred to a Capuchin friar visiting the region in 1585 and finding the temples in ruins, overgrown by vegetation. So impressed were early visitors from Europe, the Middle East, and other parts of Asia that some wildly speculated that the Romans or Alexander the Great had built the temples.

A trickle of these adventurers and traders, many of whom had settled at the court in Phnom Penh in the 16th century, began to take note of the ruins, either by hearing other people’s accounts or traveling there themselves, a 10-day journey at the time. A group of Spanish missionaries even hoped to rehabilitate the ruins and turn them into a center of Christian teaching. A Japanese interpreter, Kenryo Shimano, drew the first accurate ground plan of Angkor Wat in the early 17th century. Japanese writing on a pillar inside Angkor Wat is said to have been carved by his son, who later visited the site in honor of his adventurous father. Other foreigners—including an American, a Brit, and several French explorers—published their accounts of visiting the temples, but no one really took note.

In 1858, Henri Mouhot, a French naturalist who lived on the island of Jersey, set off on an expedition sponsored by the British Royal Geographical Society and reached Angkor in early 1860. Mouhot spent three weeks at Angkor, surveyed the temples, and continued up the Mekong River into Laos, where he eventually died of a fever (possibly malaria). His notes were published in 1864, a year after Cambodia had become a French protectorate.

RESTORATION OF ANGKOR

In 1863, a year before Mouhot’s report was published, Vice-Admiral Louis-Adolphe Bonard, the governor of the French colony of Cochin China (South Vietnam), visited Angkor and decided that it had not been the Romans or any other foreign power who had built the magnificent temples, rather the now-impoverished Cambodians.

The idea of restoring Cambodia and its people to its former grandeur encouraged the population back home in France to support the republic’s quickly expanding and unpopular colonial efforts in Southeast Asia. Angkor became a symbol of this drive, and as a consequence, it was soon very much a focus of attention at the highest levels of the French administration. Thailand was already under the influence of the British (a British photographer, John Thomson, published the first images of Angkor Wat in the 1860s), and the race was on to find a trade route into China, which was just beginning to open up to foreign commerce. Cambodia and the Mekong River were to play a key role in this race.

In 1866, the Mekong Exploration Commission, led by Ernest Doudart de Lagrée, France’s representative in Cambodia, and accompanied by Francis Garnier, Louis Delaporte, a photographer named Gsell, and several others, set off to find out whether the Mekong was navigable. On the way, they made a planned detour to Angkor and took detailed scientific notes. Louis Delaporte’s watercolors and drawings, fanciful though they were, and Gsell’s photographs of the temples along with route maps and extensive descriptions of temples and the lives of Cambodians, were published in two volumes in 1873 as Voyage d’exploration en Indo-Chine. As the French public was not aware of Henri Mouhot’s British-funded efforts, Garnier and Delaporte (Doudart de Lagrée had died by this time) got all the credit for the “discovery” of Angkor. Their findings were well presented and included, for the first time, outlying temples such as Beng Melea, Preah Khan, and Wat Nokor, east of Angkor, as well as Khmer temples in southern Laos. Of course, in the eyes of superior-minded Europeans, the temples could not compete in grandeur with efforts back home, and the early explorers claimed that “Cambodian art ought to perhaps rank its productions behind the greatest masterpieces in the West.”

But slowly, in the minds of these early archaeologists and consequently the French public, the true dimensions of the Khmer Empire began to emerge. In 1867, at the Universal Exposition in Paris, visitors were presented with giant plaster-cast reproductions of the temples. In the following years, Delaporte returned to Cambodia and began to systematically remove statues, sculptures, and stonework to Europe. Soon after, he became the director of the Indochinese Museum in Paris, which began to amass a collection of Angkorian artifacts. Around the same time, the first tourists began to arrive. They also took souvenirs with them, many of which disappeared into private homes in France. In 1887, the French architect Lucien Fournereau made extensive and detailed drawings of Angkor Wat and other temples that, for the first time, presented Europeans with accurate scientific representations of Khmer architecture. Hendrick Kern, a Dutchman, managed to decipher the Sanskrit inscriptions on temple walls in 1879, and the French epigraphist Étienne Aymonier undertook a first inventory of the temples around Angkor, listing 910 monuments in all.

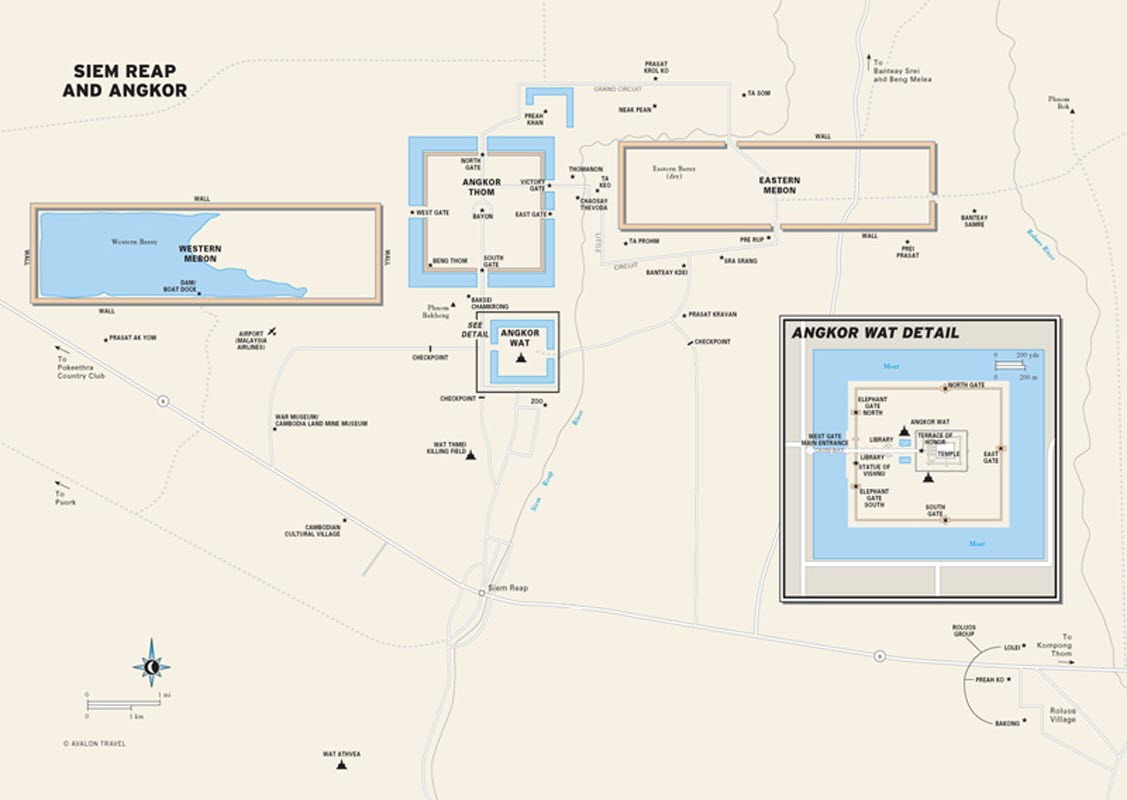

In 1898, the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), founded by the colonial masters to study various aspects of their Far East possessions, began to work in Cambodia, and soon efforts were made to start clearing the forest from some of the ruins. The EFEO created a road network around the ruins, the Petit Circuit and the Grand Circuit, which are still used by many visitors. To this day, the EFEO has been the body most consistently involved in the study and restoration of Angkor.

The Cambodians were never consulted about any of France’s activities around Angkor. The French writer Pierre Loti remarked in 1912 that France “was idiotically desperate to rule over Asia, which has existed since time immemorial, and to disrupt the course of things there.” He felt that the French presence was disrupting the continuity of Cambodia, where the royal dancers appeared to step out of the past into the present, unchanged by time. Loti said, “Times we thought were forever past are revived here before our eyes; nothing has changed here, either in the spirit of the people or in the heart of their palaces.” The French artist Auguste Rodin was so taken with the dancers that he followed them around France on their visit in 1906.

At the time, Angkor, in Siem Reap Province, still belonged to Siam. It was only in 1907 that France forced Siam to hand over three provinces that had been under Siamese control, including Siem Reap. From then on, France, the colonial masters of Indochina, were in control of the temple—until the beginning of World War II, when the area briefly returned to Siamese control, because Siam had aligned itself with the Japanese, who had wrested control of the colonies from the French (although officers from the collaborating Vichy France government continued to administer the rest of Cambodia).

Following World War II, France regained control of Cambodia and the Angkor temples until independence in 1953. This long-term continuity meant that the EFEO had a total monopoly on the research conducted on Angkor, which enabled the scientists involved to develop a coherent body of work over the years. In 1908, Conservation d’Angkor, the archaeological directorate of the Cambodian government, was established in Siem Reap and became responsible for the maintenance of the ruins. The office’s first curator, Jean Commaille, originally a painter who had arrived with the Foreign Legion, lived in a straw hut by the causeway to Angkor Wat, and wrote the first guidebook to Angkor before being killed by bandits in 1916.

Commaille’s successors further cleared the forest, and, in 1925, Angkor was officially opened as a park, designed to attract tourists. Soon the first batches of foreign visitors arrived by car or by boat from Phnom Penh or Bangkok, and guided tours on elephant back were conducted around the temples. Many of these early tourists, for the most part rich globe-trotters, stole priceless items from among the ruins or carved their names into the ancient stones. Little could be done about the thefts except to search a few posh hotel rooms. Tourism continued to increase, and in 1936 even Charlie Chaplin did a round of the temples.

In the meantime, the EFEO’s research techniques continued to evolve and became more integrated. Initially, different specialists had worked on different aspects of reconstruction and research; it was only in the late 1920s that several disciplines were combined—with spectacular results. Now the Bayon and Banteay Srei could properly be dated, and Angkor’s chronology finally took shape. Influenced by the Archaeological Service of the Dutch East Indies, the EFEO, under curator Henri Marchal, began to undertake complete reconstructions of temples in the 1930s, most notably of Banteay Srei. Following World War II, as Cambodia moved toward independence, the EFEO moved its headquarters to France, and Conservation d’Angkor now ran the largest archaeological dig in the world, with the French staff slowly being complemented by French-educated students from Phnom Penh. Excavations could now be undertaken farther afield at locations like Sambor Prei Kuk, the pre-Angkorian ruins near Kompong Thom.

In the 1960s, Angkor began to be used as a backdrop for movies, most notably Lord Jim and some of King Sihanouk’s feature films. The ever-growing popularity of the temples meant that looting increased, and many statues had to be removed and replaced with plaster copies.

Soon there were new challenges to the continuing restoration efforts—war was coming. Following Sihanouk’s fall from power in 1970, the French staff of the EFEO carried on working on the temples for another two years, until they were forced to leave as the Khmer Rouge were closing in. Local workers continued with their efforts until 1975, when the revolutionary communists forced them into the fields to work or executed them. Angkor was once again abandoned. Through the long years of communist revolution and the subsequent civil war, the temples remained off-limits both to researchers and casual visitors, and the forest grew back over the monuments. The Khmer Rouge was too superstitious to destroy the temples, even though they destroyed virtually every modern temple in the country, but many research documents went up in flames. Luckily, much of the work the EFEO had done since its inception, some 70 years of solid systematic research, had been copied and taken to Paris.

Following the invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam, work slowly resumed in the 1980s. First, the Archaeological Survey of India sent a team to restore Angkor Wat. The efforts of this enterprise have been widely criticized, but it should be kept in mind how very dangerous a country Cambodia was at the time, and that the Indian scientists had few materials and few local experts to work with. At the same time, a Polish scientific delegation engaged in excavations around the Bayon. In 1989, the Royal University of Fine Arts was reopened in Phnom Penh in order to train a new generation of archaeologists.

In 1991, after 20 years of neglect and devastation, not just of the ruins of Angkor but of Cambodia as a whole, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) established an office in Cambodia. Soon after, the World Monuments Fund was the first NGO to establish a branch at Angkor, followed shortly after by the return of the EFEO. France and Japan soon pledged large funds for safeguarding the ruins, which by now were once again being looted at a frightening rate. Through the 1990s, new information garnered with technologies not available prior to 1972, including aerial photographs and even space-based radar images obtained by NASA’s space shuttle Endeavour, began to be systematically assimilated into the larger body of research.

In 1992, Angkor Wat, along with 400 other monuments in the area, was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This officially made Angkor one of the world’s most important cultural sites, a move designed to protect the remnants of the Khmer Empire from further looting or indiscriminate development.

Cambodia now has an article in its constitution that calls on the state to preserve the country’s ancient monuments. UNESCO is the international coordinator for overseas contributions to the upkeep of the temples. While restoration efforts have continued, and while UNESCO has been pushing for sustainable development, in 1995 the Cambodian government created the Authority for the Protection and Management of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap (APSARA), an NGO in charge of research, protection, and conservation of cultural heritage as well as urban and tourist development.